Know thy enemy

Let's start with an overview

We suggest you first get an overview by having a look at this video:

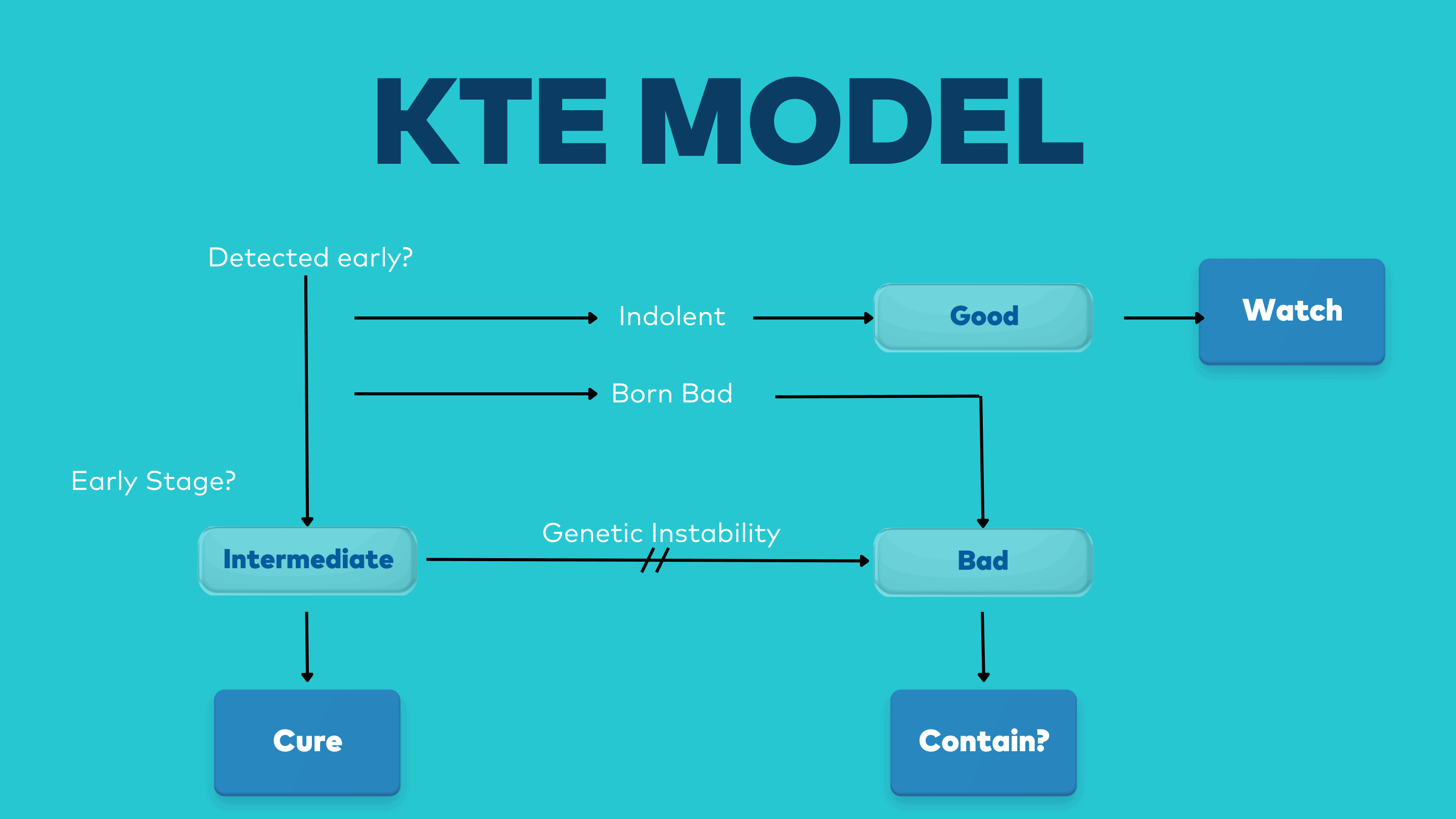

There are two main outputs from this video, what we have called the KTE Model, and the KTE roadmap.

The KTE model shows, in broad terms, how each of the three classes of cancer arise, each with their main treatment objective.

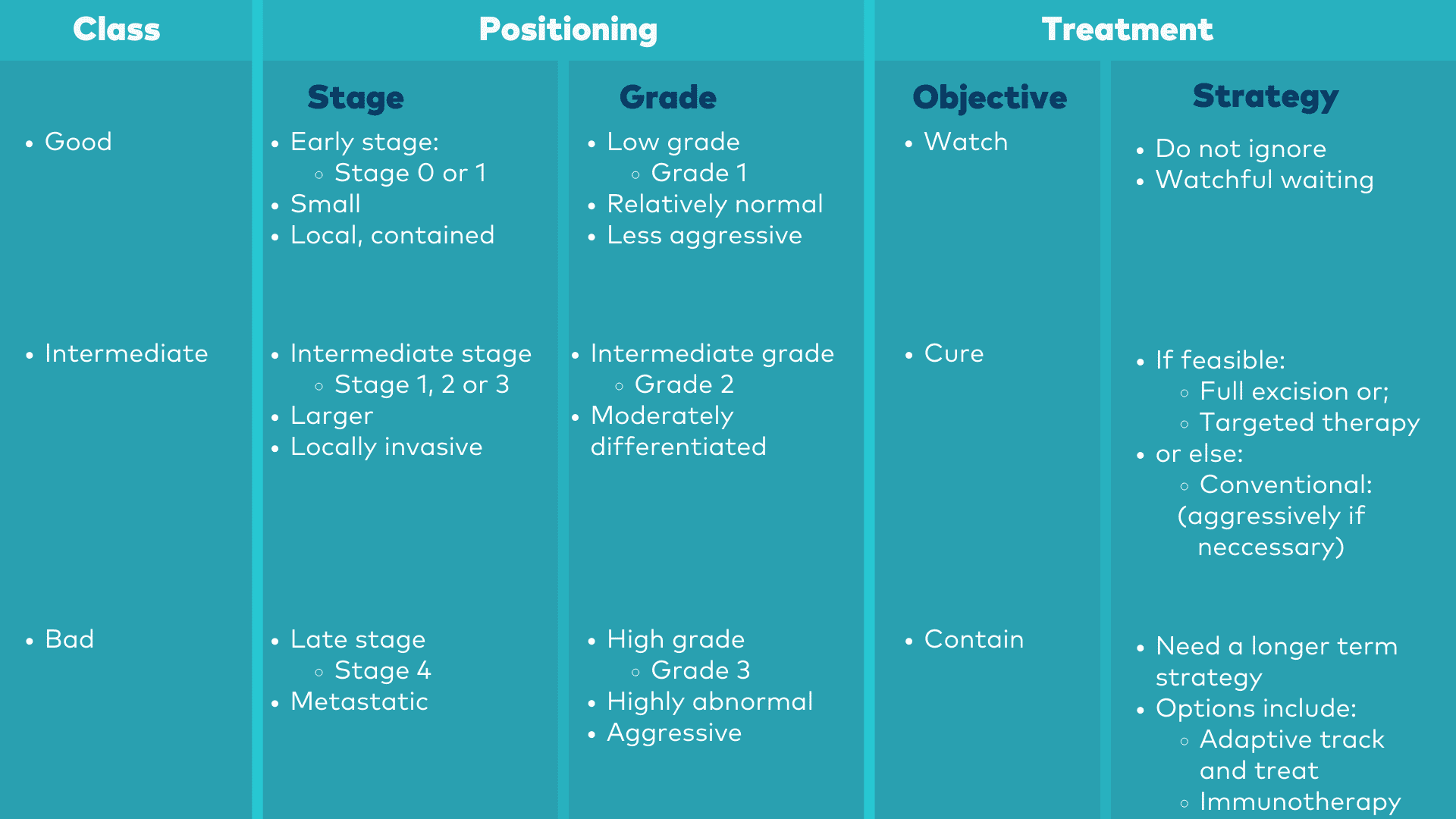

The KTE roadmap helps you to position a particular cancer in relation to the three classes, along with treatment implications.

The KTE Model

The KTE Roadmap

So how then do you proceed for your own particular cancer?

The first step is to determine in which class your cancer belongs; that is, you need to "Position" your cancer. As we will describe later below, that primarily requires two key numbers which your doctor will get from your pathology report, which are the stage and the grade of your cancer. With these two numbers you can then identify the class of your cancer from the roadmap above,

Once it is positioned, you can then focus in on your own particular class of cancer:

A GOOD cancer is usually found during early detection, or as an

accidental result of some other procedure such as an examination or a scan.

It is potentially indolent; very slow growing, and unlikely to

progress to a high-grade malignancy during an average human life span.

In terms of positioning it is early stage and low grade.

It should not be treated and should rather be actively WATCHED.

INTERMEDIATES are earlier stage cancers which are not indolent and

need to be treated.

It has moderately abnormal cells (medium grade); is relatively stable

(mutating and evolving slowly); and homogeneous.

It is therefore unlikely to develop any significant resistance to

treatment.

Intermediates are eminently treatable and should be treated with the

objective of CURE.

BAD cancers usually arise from intermediates that are either not

treated or else recur following treatment

(though there are some bad cancers that are genetically unstable from birth, so

called Born to be Bads).

Bad cancers are high grade; genetically unstable; heterogeneous; and

evolving fast.

They are late stage and more than likely metastatic.

Bad cancers are therefore highly resistant to treatment and very

difficult to treat.

They have limited chance of cure and should be treated with the

objective to CONTAIN.

(Note, however, we will show that the possibility of some cures is starting to emerge in some cases).

So now .....

If you are in a hurry to learn more about your particular class of cancer, then just click on the appropriate link (in blue above) for your class.

If you would prefer to rather understand more about cancer first, then you can continue reading.

What exactly is Cancer?

Cancer is a disease which starts when damaged cells divide without control. Cancer is essentially a disease of

the genes. In broad terms, this is how it happens:

The cells of our body are constantly at work. They need to

grow and divide in order to maintain and repair the body. In normal

circumstances this occurs under the strict control of processes within the

cells and their surrounding environment.

Cancer occurs when some of the genes driving and controlling

these processes get damaged (mutated) and start dividing uncontrollably.

There are two types of genes which both need to be damaged

for cancer to be initiated; drivers of cell division, the so-called proto-oncogenes

(foot stuck on the accelerator); and controllers against excessive

proliferation, the tumour suppressor genes (brakes fail). There are two

important consequences of this:

1. More than one mutation in cancer-inducing genes

is required to initiate cancerous growth, and

2. Every cancer starts as an expansion from a

single damaged (rebel) cell.

How Cancer cells behave

But there are other important features which cancers develop

as they progress:

Firstly, there is malignancy, and it is a major reason that

some cancers are so very dangerous. A malignant cancer is one which has invaded

nearby tissue and possibly spread (metastasised) to other parts of the body to

form new tumours.

Furthermore, as cancers advance, they become heterogeneous. At the outset all cancers are genetically homogeneous, all cancer cells sharing the same mutations. See this as the trunk of a tree. But eventually, at some point a Rubicon is reached (in some tumours a lot sooner than others) when one of the tumour cells becomes genetically unstable. The clone growing from that unstable cell then starts mutating at a much faster rate and the tree starts branching. The cancer is then heterogeneous and evolving, and far more difficult to treat.

It is also important to understand that the immune system is

not blind to cancer. It can exert control over the growth of tumours. Indeed, in some cases it can eliminate

tumours. However, as cancers progress, they often evolve defences as protection

against the immune system.

Cancers form a complex and highly variable group of

diseases:

The number of genes that, when mutated, can contribute to cancer, run into the hundreds (and is growing); and each gene can be mutated in a number of ways. In any given patient, a subset of these genes must be mutated for the cancer to progress, a process that occurs sequentially over a number of years. The number of possible combinations of such mutations is thus huge. In effect, cancer is not one disease - but a cluster of diseases with hundreds of subtypes.

Indeed, at the genetic level, each and every cancer is

unique.

Traditional types of Cancer

Firstly, there are two main categories of cancer: hematologic

(blood) cancers such as leukaemia; and solid cancers such as breast and

prostate cancers. Surgery, for instance, is not an option for blood cancers.

The next level of classification is that of the main groups

of cancer. For example, a common split is between carcinoma (external and

internal surface lining), sarcoma (supportive and connective tissue including muscle

and bone), leukaemia (blood), and lymphoma (lymphatic system). See, for

example: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

and click on types of cancer,

If you want to gain an understanding of your specific cancer

type, we recommend the National Cancer Institutes A-Z listing contained in https://www.cancer.gov/types, where

over 100 specific cancers are described.

In terms of treatment, there are 3 main classes of cancer

Cancer is not cancer is not cancer. It’s like there is

cancer and then there is CANCER. That is why it is important for you to

understand your particular cancer. You need to understand exactly what you are

dealing with.

Good, Intermediate and Bad

Start by recognising that, from a treatment point

of view, there are three main classes of cancer. This is not just our opinion.

Here is a quote from the leading textbook on cancer (Robert A. Weinberg, The

Biology of Cancer):

“The complexity of the decision to proceed with treatment

should ideally confront the fact that diagnosed tumours fall into three classes.”

In the book we draw off Weinberg’s work and, for

convenience, call these three classes the “Good”, the “Intermediates” and the

“Bad”.

Good Cancers

A “Good” cancer is usually found during early detection, or

as an accidental result of some other procedure such as an examination or a

scan. A “Good” cancer is one that is potentially indolent;

very slow growing, unlikely to progress to a high-grade malignancy during an

average human life span and need not be treated.

Intermediate Cancers

An “Intermediate” is one with moderately abnormal cells, is

genetically relatively stable (mutating and evolving slowly), homogeneous, and unlikely

to develop any significant resistance to treatment. An intermediate offers a good chance of cure.

Bad Cancers

A “Bad” cancer is advanced, genetically unstable (mutating

and evolving fast), heterogeneous and prone to resistance when treated. It is

probably also metastatic and has limited chance of cure.

So, although each cancer is unique, from a treatment point

of view there are also commonalities. What we now want to do is to identify the

key information you need to know in order to characterise your cancer from a

treatment point of view. We call this “positioning”.

Once you have this understanding you will be in a far better

position to discuss treatment options for your particular cancer with your

doctor.

Staging, Grading & Class

The first step is to determine which of the three treatment classes your cancer belongs to.

There are two numbers from your pathology report which are key to this classification: the stage of your cancer and the grade.

|

Class |

Stage |

Grade |

|

“Good” |

0 or 1 |

|

|

“Intermediate” |

1 to 3 |

2 |

|

“Bad” |

4 |

3 |

Your doctor will discuss your pathology report with you as

part of your diagnosis. This is a very important report and it is important that

you try to understand the relevance of what is in it. In particular, your

doctor will put a lot of emphasis on the stage and the grade of your cancer.

The specifics vary depending on the type of cancer, but in

broad terms:

Stage refers to the extent of your cancer, such as how large

the tumour is, and if and how far it has spread. The scale ranges from Stage 0

(a precancer), through stages 1 to 3 (cancer is present - the higher the

number, the larger the cancer tumour and the more it has invaded into nearby

tissues) to the highest, the notorious stage 4 (cancer has spread to distant

parts of the body, i.e., it is metastatic).

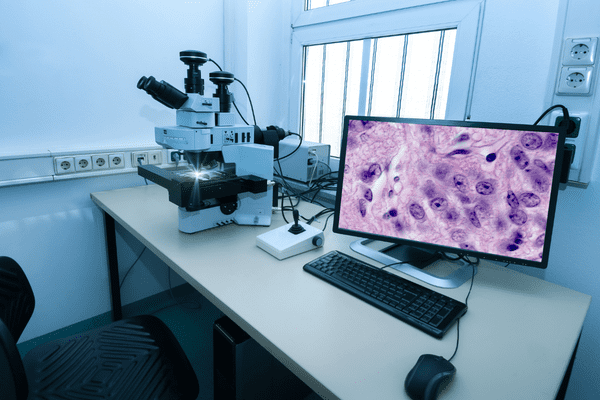

The grade of a cancer is based on the appearance of the

cancer cells under the microscope. It is a description of the tumour based on

how abnormal the tumour cells and the tumour tissue look under a microscope,

and is an indicator of how quickly a tumour is likely to grow and spread (aggression). Lower

grade cancer cells (grade 1) look relatively normal (well differentiated) and

are growing more slowly, grade 2 is intermediate grade (moderately

differentiated), while grade 3 is high grade, poorly differentiated and more

aggressive.

You can then map the stage and grade of your cancer to one

of the three classes we defined above. This is a critical step and warrants

discussion with your doctor. Note, however, that the terms “class of cancer”,

as well as “Good”, “Intermediate” and “Bad” cancers, are our own terms and not

terms a doctor will be familiar with. Nevertheless, they will help you shape your

discussion with your doctor.

This is an important milestone in the positioning of your cancer. But there are two other key indicators you should be looking for, especially if your cancer is “Intermediate” or “Bad”:

Is your cancer targetable?

Is your cancer immunogenic?

(Note

that if your class of cancer is “Good” then you can skip the rest of this section

and proceed immediately to your treatment options below)

Genetics: Is your Cancer targetable?

We saw that cancer is caused by mutation to genes controlling

the process of cell division. These are called driver genes. For some (by no

means all) cancers, driver genes can be identified for which specific targeted

drugs are available. These mutations are identified using a technology called

genetic sequencing and this is fast becoming a major addition to the armoury of

cancer diagnosis.

Targeted drugs are highly specific to the driver mutations and

therefore have fewer side effects. Another advantage is that they can often be

taken in pill form. This is a fairly recent addition to the cancer armoury with

the first targeted drug approved in 2001.

Targeted therapies are particularly useful if your cancer is

an “Intermediate” (which is homogeneous, and stable and therefore less likely

to develop resistance), but can also be useful in some “Bad” cancers.

The need and the possibility for the genetic sequencing of

your tumour is a conversation you definitely should have with your doctor. It

is important that you raise this – in the book we report recent surveys which

show that less than 50% of community-based oncologists are using genetic

testing to guide patient discussions about treatment in the US (in contrast

with over 70% of academic clinicians). You may do a bit of research before-hand – Google

“targeted therapy" for your cancer type.

If your cancer is sequenced then, not only can you look at

possible targets, but you can also get a feel for how mutated your cancer is (called

tumour mutational burden or TMB). High TMB can be an indicator of whether your

cancer is heterogeneous, but, more importantly, it is a measure of

immunogenicity, which we turn to next.

Is your Cancer Immunogenic?

Immunotherapy is the most recent addition to the cancer

treatment armoury. It doesn’t kill the cancer directly but rather releases the

brakes on the immune system so that the immune system can then kill the cancer. It

is an important addition because the immune system has

the capacity (in the book we use the concept of “variety”) to counter a

heterogeneous, evolving and metastatic cancer. And, indeed, it has already shown curative potential for a number of advanced, metastatic cancers.

So, it is also important for you to explore this option with your doctor, especially if you have a “bad” cancer. Ask your doctor whether there are any indications that the tumour may be visible to the immune system (immunogenic) and whether any further testing in this regard would be warranted.

Key indicators of immunogenicity are:

Tumour mutational burden

The tumour has a higher tumour mutational burden (TMB), and

hence a higher number of targets for the immune system to see. There are, for

example, cancers which have high TMB due to environmental damage (smoking or UV

damage to skin). But another important contributor to high TMB is damage to DNA

repair genes, either inherited or acquired; e.g., damaged BRCA genes, as well

as a condition called micro-satellite instability MSI, both of which can be

determined from genetic testing.

Immune checkpoint expression

A second indicator of immunogenicity is higher levels of

so-called immune checkpoint expression (especially the so-called PD-1 and PD-L1

checkpoint biomarkers); a measure of the level of the defences the tumour has

built up against immune system.

Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes

Another measure is that of so-called tumour infiltrating

lymphocytes (TIL’s). This looks at the presence and activity of the immune

cells in and around the tumour, and is used to determine if the tumour is hot

or cold (a hot tumour is more inflamed and has a higher presence and activity

of immune cells infiltrating the tumour, and this is a good indicator for the

use of immune checkpoint immunotherapy).

Immunotherapy is a very important and fast-growing new

treatment modality and is quite extensively covered in the book.

Once

all the information is available and your tumour is clearly positioned, you can

start looking at your treatment options with your doctor. We now look at the

more general, high-level treatment issues you could pursue with your doctor. There

is a separate section for each class of cancer and you need only read the

section appropriate to your specific class.

"Good" Cancer

A “Good” cancer is usually found during an early detection

process, or as an accidental result of some other procedure such as an

examination or a scan. It is potentially indolent.

Why do we say potentially? A (true) indolent is very slow

growing, unlikely to progress to a high-grade malignancy during an average

human life span and need not be treated. There is an issue, however. Currently,

early detection processes are not sufficiently precise to be able to

confidently discriminate between the “pussy cats” (true indolents) and the

“tigers” (the low grade, but potentially lethal growths that will, sooner or

later, progress).

There are two possible responses to this uncertainty:

“Just cut it out anyway, out of sight is out of mind”. However, this response comes with a significant risk of overtreatment, subjecting one to the unnecessary stress, trauma and cost of treating something that may never cause a significant problem (and, indeed, as we note in chapter 4 in the book, may even increase the risk of the cancer growing).

At the same time, it can’t just be ignored. Given the

uncertainty in identifying true indolents, there remains a risk that it will

progress. So, the alternative response is not to just ignore the tumour, but rather

to undertake a regular and on-going process of “watchful waiting”, in case it

starts turning nasty. Watchful waiting is a systematic and routine programme of

checking and testing to determine whether there is any evidence that the growth

is starting to progress (an example for prostate cancer can be found in the

book, chapter 4).

What to discuss with your doctor

So, if your cancer is “Good” (early-stage, low grade and potentially indolent) then here are some key issues for discussion with your doctor:

* What evidence is there that your tumour may be truly

indolent? Are there any concerns that it may not be? What are the probabilities?

* What would treatment to eliminate the tumour entail? What

are the benefits? What are the risks? Are there potential side effects, both

short term and long term?

* What would be involved in a watch-and-wait strategy? How would it be done and what would be the logistics?

* Would a ‘watch and wait’ strategy increase the risk or reduce the options if the tumour were to start progressing and had to be removed later?

With a treatment plan of ‘watch and wait’, there are also some

particular logistical issues:

* Make sure your health insurance would be on-side, preferably

through a chronic care arrangement.

* Discipline, discipline, discipline. Stick with the plan, meet your commitments, don’t ever feel that you are done and can discontinue the programme.

"Intermediate" Cancer

An “Intermediate” is a tumour with moderately abnormal cells.

It is genetically stable (mutating and evolving slowly), homogeneous, and unlikely

to develop any significant resistance to treatment. These cancers are eminently

treatable and offer a good chance of cure.

What does cure mean for an “intermediate”? If the cancer can

be fully excised through surgery, then game over.

If genetics identify a targetable driver mutation, the targeted therapy may well be a daily pill leading to long-term chronic containment of the disease, if not total elimination (with possible migration to a related but different pill if late resistance does occur).

If treated conventionally (some or all of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy), then treatment should, if necessary, err on the side of aggression lest some cancerous cells escape and start evolving into a more advanced cancer. Remember, the objective here should be total remission. (A case study can be found in the book illustrating such appropriate aggression – ‘Liza: Appropriate aggression in search of a cure’ in Chapter 5).

What to discuss with your doctor

Here, then, are some key questions you should be asking your

doctor if your cancer is in the intermediate class:

Get a clear understanding of the treatment objective. If the

objective is anything less than cure then challenge this and ask for reasons

why not. Get a second opinion if you feel unconvinced.

Is it possible to cut the tumour out? If so, is there any

risk that it can’t all be taken out? Should the surgery be supplemented with

any other treatment as insurance? Complete excision with surgery is first

prize, but remember, if just one cancer cell is left behind then the cancer

will likely recur (in the same way that the original cancer started for a

single cell).

If full excision is not possible, then ask about the

genetics? If genetic testing has not yet been done, then question this? If

testing has been done, then do your genetics show any of the known, targetable

mutations? What prognosis is foreseen with targeted treatment (noting that an

intermediate cancer is homogeneous and unlikely to develop significant

resistance to targeted treatment).

If it is not targetable, then the treatment proposal will

probably be conventional. Ask whether the proposed treatment is a standard

of care and the expected prognosis. And, as said before, if you feel there

is any uncertainty, then err on the side of aggression.

Immunotherapy is not yet standard for earlier stage cancers,

although trials are in progress. It is usually not necessary to consider a

trial for an “Intermediate” cancer.

The logistics of treating Intermediate Cancer

For an “Intermediate”, treatment should be relatively

standard and you can select an appropriate and convenient specialist from

private practice to lead your treatment; preferably one open to shared decision

making.

Under these circumstances, health insurance should not

present any issues, but try to keep them in the loop throughout.

"Bad" Cancer

A “Bad” cancer is advanced, genetically unstable (mutating

and evolving fast), heterogeneous and is prone to resistance when treated. It

is also likely to be metastatic. Cure with conventional treatments is not very likely.

“Bad” cancers need a different mind-set. They evolve

and change over time in response to treatment. You need to prepare for the long

haul. It’s a war rather than a battle. In your discussions with your doctor,

you should be thinking strategy, not just treatment.

What do we mean by strategy? In chapter 6 of the book, we

sketch out a strategy we call ‘active waiting’ as an example. This consists of

a process of adaptively controlling the cancer (rather than, probably futilely,

trying to aggressively destroy it), while keeping an active watch for a ‘next

new thing’ which may have curative potential for your particular cancer.[1]

[1] Remembering,

for instance, that the powerful new treatment of immunotherapy was a ‘next new

thing’ just 10 years ago, and the next phase of this modality, called

combination immunotherapy, is already well into clinical trials (see Chapter 9

in the book).

What to discuss with your doctor

The initial offering from your doctor will in all probability be the standard

of care for your cancer. Interrogate this approach, understand it, but don’t

just blindly accept it. What is the treatment objective? Is cure possible? What

is the 5-year survival rate? What are the main side-effects, both short term

and long term? What happens if (when) it stops working due to resistance?

Then explore other possible opportunities with your doctor:

Does your genetic testing show any of the more well-known

driver mutations? What role could targeted therapies play in your strategy?

Furthermore, targeted treatments could be used as part of

the control process of the ‘active waiting’ strategy on an adaptive ‘track and

treat’ basis (section 9.2 in the book for more on ‘track and treat’).

What is the medical evidence for immunotherapy for your type

of cancer? How immunogenic is your tumour? Is immunotherapy a serious option? (Remember

that immunotherapy has shown the potential to cure some advanced (“Bad”)

cancers; much more on this in chapters 6 and 9 in the book).

Once all this information is in place, then we propose one

more very important step before you make a final decision. Seriously consider

the option of a second opinion through an academic or research hospital. A

number of the larger such institutions in the US, for instance, offer this

service on a virtual basis (try googling “virtual second opinions for cancer”).

This will help broaden your options based on the latest

evidence for your specific cancer. As part of this process, you could also explore

the options arising from clinical trials. You could also explore the

possibility of an on-going virtual collaboration between your doctor and the academic/research

institution consulted, especially if your cancer is of research or academic

interest to them. If not of interest to them, ask whether they can identify

another institution where there could be such interest.

The logistics of treating a Bad Cancer

The logistics of your treatment also require a quantum shift

if your cancer is “Bad”.

We have already spoken of a possible collaboration with an

academic/research hospital. More than likely multiple specialities will be

involved in your treatment. In which case you could also consider being treated

in a one-stop shop for cancer care which could probably offer a better, more

co-ordinated treatment option.

You would also need to work closely with your health

insurance consultant (and a financial navigator at the hospital) to find out

what options they would or would not support. The treatment may have to be

adaptive, tracking the cancer as it evolves, requiring on-going participation

of the key parties, so try to keep an advisory team together.

Planning for the long haul

You may well also need to set up personal plans for the

long-haul and it helps to think logically about these:

- Possible relocation?

- A sound financial plan.

- Resources for emotional support.

- A support network.

If your cancer is “Bad”, don’t just jump into the first

option that is put on the table. You need to explore all options (and the

second opinion proposal will certainly help broaden the horizons). A war requires strategy and is not all about

just winning the next battle.

In researching the latest developments in immunotherapy,

Colin came to the conclusion that if he were to be diagnosed with an advanced

cancer then he would pursue immunotherapy (including possible trials arising from

the new horizon combination IO if necessary) as his preferred treatment option.

This argument is detailed in a blog: